Aquí algo de lo mío....

31.12.12

29.12.12

Carmen Guerrero, para un "deber ser" gubernamental

A partir de enero de 2013 el Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales contará con una nueva Secretaria: Carmen Guerrero Pérez. No hay forma de hacer un buen análisis si no se mira atrás unas cuantas décadas y se examina la trayectoria tanto de Carmen como del contexto de controversias y movimientos sociales en el eje medioambiental en Puerto Rico. El asunto puramente partidista me interesa menos, los grupos de interés que han dictado la agenda mucho más. Digamos esto por ahora: Además del mérito y la respectiva preparación y experiencia, ocupar una secretaría de gabinete implica, entre otras cosas, implantar y fomentar la política pública de la agencia y velar por que su Ley Orgánica se cumpla, ser la voz de esa política pública en la Rama Ejecutiva y ante el Gobernador, reconocer a los sectores y grupos de interés y saber aglutinar fuerzas y energías en la agencia para que funcione.

Para esto se necesita tener claro lo que significa hoy día ser una funcionaria pública (el deber ser del servicio público) saber escuchar, tener liderato -sin que eso implique arbitrariedad- y tener un compromiso genuino con el bienestar común y el interés público, todos conceptos muy maltrechos y que necesitan reivindicación. Quizás lo más que necesita reivindicación en estos momentos es el sentido de confianza, la sensación de que al mando de esa institución gubernamental, hay alguien verdaderamente íntegro, capaz de apalabrar con firmeza las necesidades del país y que pueda sentirse que esa persona nos representa. Y ese sentido de confianza no se busca en aras de descansar en el ejercer ciudadanía, sino para la posibilidad de ejercerla aún mejor y más efectivamente.

Carmen Guerrero Pérez para mí reúne estas características y puedo decir desde este blog, que siento que ella, su voz allí, representa un nos del cual me siento parte. Pero mejor aún, sus oídos allí, representan la posibilidad de disentir y ella cuenta con la inteligencia y sensibilidad de saber escuchar. Tanto lo primero, como lo segundo son importantes. Carmen, voz y oídos, corazón e inteligencia, marcan un nuevo ciclo de quehaceres intensos, al menos en la política pública ambiental. No hay que dejarla sola, al contrario, hay que ejercer la ciudadanía aún más intensamente.

16.12.12

13.12.12

Regala el comienzo de una conversación, regala "Derecho al Derecho"!

En estos días de fiesta, si vas a hacer un regalo, regala el comienzo de una conversación importante para nuestro país y para nuestro mundo de vida común. Pensemos juntos en nuestras instituciones jurídico-políticas, en el estado de nuestro acceso a la reivindicación de los derechos.

Regala esta nueva publicación Derecho al Derecho: intersticios y grietas del poder judicial en Puerto Rico y con este regalo amplía la gama y pluralidad de los y las participantes en este proyecto-conversación. Derecho al Derecho está disponible en:

-Librería Mágica (Río Piedras)

-Norberto González (Río Piedras)

-Tertulia Viejo San Juan

-Libros AC (Santurce)

-Escuela Derecho UPR (UPR-Río Piedras)

-Bibliográficas

-Coop Inter Metro

-Universidad Católica Ponce

-Página Web de EEE

-Amazon

Derecho al derecho: intersticios y grietas del poder judicial en Puerto Rico es una invitación audaz al diálogo sobre lo jurídico y a la participación activa de la ciudadanía en ese esfuerzo. El sistema judicial en Puerto Rico ha sido secuestrado, nos advierte. Es preciso rescatarlo de la del contubernio político-partidista y traerlo a la esfera del debate público crítico. Es urgente que cada persona ejerza su ciudadanía en la esfera del poder judicial no solo reclamando cuentas y exigiendo decisiones razonadas y ponderadas, sino siendo sujetos de la esfera judicial dialógica que es posible en las mejores democracias.

El espacio digital (www.derechoalderecho.org) y las comunidades que propicia son el pretexto para una apuesta por la construcción de la esfera jurídica en Puerto Rico desde todas las esquinas. La Rama Judicial –compuesta por abogadas/os y juezas/ces en su mayoría– debe estar atenta a la ciudadanía y a la academia jurídica para poder descargar sus gestiones responsable y justamente. Pero, sobre todo, para ajustarse a la vanguardia de los tiempos y traslucir su voluntad por un mejor país.

Érika e Hiram se dan a la tarea de iniciar estos diálogos –en la mejor tradición socrática–, sin dejar a nadie fuera de la convocatoria. Esta tertulia es para los oponentes y para los simpatizantes del estado actual del poder judicial en el país. Es para los estudiantes y los profesores. Es para el experto y el aficionado del Derecho. Es para ti, lectora y lector que reclamas una ciudadanía participativa todos los días.

Derecho al derecho… es una apuesta por la democratización radical de lo jurídico y, a la vez, es una crítica aguda y firme sobre la realidad actual del poder judicial, tan distante del ideal al que se aspira. El punto final, es el comienzo de una historia contemporánea del derecho en nuestro entorno jurídico y un punto suspensivo en espera de otros diálogos por venir.

12.12.12

La configuración de un arte de la vida

"Sigo leyendo a Bennett, y reconozco en él cada vez más a un hombre no sólo cuya actitud es actualmente similar a la mía, sino que además sirve para reforzarla: un hombre en realidad en el que una absoluta falta de ilusiones y una desconfianza radical respecto al curso del mundo no conducen ni al fanatismo moral ni a la amargura, sino a la configuración de un arte de la vida extremadamente astuto, inteligente y refinado que le lleva a sacar de su propio infortunio oportunidades y de su propia vileza algunos de los comportamientos decentes que competen a la vida humana".

Le escribe Walter Benjamin a Jula Radt, en sus Cartas de Ibiza.

8.12.12

The venture into the public realm (H. Arendt)

Gaus:

Permit me a last

question. In a tribute to Jaspers you said: “Humanity is never acquired in

solitude, and never by giving one’s work to the public. It can be achieved only

by one who has thrown his life and his person into ‘the venture into the public

realm’”. This ‘venture into the public realm’ -which is a quotation from

Jaspers- what does it mean for Hannah Arendt?.

Arendt:

The venture into

the public realm seems clear to me. One exposes oneself to the light of the

public, as a person. Although I am of the opinion that one must not appear and

act in public self-consciously, still I know that in every action the person is

expressed as in no other human activity. Speaking is also a form of action.

That is one venture. The other is: we start something. We weave our strand into

a network of relations. What comes of it we never know. We’ve all been taught

to say: Lord forgive them, for they not know what they do. That is true of all

action. Quite simply and concretely true, because one cannot know. That is what is meant by a venture. And now I would

say that this venture is only possible when there is trust in people. A trust

–which is difficult to formulate but fundamental—in what is human in all

people. Otherwise such a venture could not be made.” (1964).

Hannah Arendt, Essays in Understanding (1994), pp.

22-23.

4.12.12

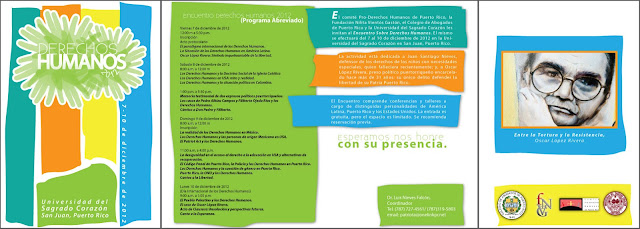

Encuentro de Derechos Humanos 2012

Encuentro de Derechos Humanos 2012 (por la Excarcelación de Oscar López Rivera, dedicado a la Memoria de Juan Santiago Nieves)

7 al 10 dic en la Universidad del Sagrado Corazon

Pulsa para el Programa y más detalles.

3.12.12

Prejudice Against Politics

“Prejudice

Against Politics and What, In Fact, Politics is Today.

Any talk of

politics in our time has to begin with those prejudices that all of us who aren’t

professional politicians have against politics. Our shared prejudices are

themselves political in the broadest sense. They do not originate in the

arrogance of the educated, are not the result of the cynicism of those who have

seen too much and understood too little. Because prejudices crop up in our own

thinking, we cannot ignore them, and since they refer to undeniable realities

and faithfully reflect our current situation precisely in its political aspects,

we cannot silence them with arguments. These prejudices, however, are not

judgments. They indicate that we have stumbled into a situation in which we do

not know, or do not yet know, how to function in just such political terms. The

danger is that politics may vanish entirely from the world. Our prejudices

invade our thoughts; they throw the baby out with the bathwater, confuse

politics with what would put an end to politics and present that very

catastrophe as if it we inherent in the nature of things and thus inevitable.

Underlying our

prejudices against politics today are hope and fear: the fear that the humanity

could destroy itself through politics and through the means of force now at its

disposal, and linked with this fear, the hope that humanity will come to its

senses and rid the world, not of humankind, but of politics. It could do so

through a world government that transforms the state into an administrative

machine, resolve political conflicts bureaucratically, and replaces armies with

police forces. If politics is defined in its usual sense, as a relationship

between the rulers and the ruled, this hope is, of course, purely utopian. In

taking this point of view, we would end up not with the abolition of politics,

but with a despotism of massive proportions in which the abyss separating the

rulers from the ruled would be so gigantic that any sort of rebellion would no

longer be possible, not to mention any form of control of the rulers by the

ruled. The fact that no individual ---no despot, per se--- could be identified

within this world government would in no way change its despotic character.

Bureaucratic rule, the anonymous of the bureaucrat, is no less despotic because

“nobody” exercises it. On the contrary, it is more fearsome still, because no

one can speak with or petition this “nobody”.”

-Hannah Arendt, “Introduction

into Politics”, in The Promise of Politics (Shocken Books, NY,

2005), pp. 96-97.

2.12.12

Carta de Agamben a Arendt

"I am a young writer and essayist for whom discovering your books last year has represented a decisive experience. May I express here my gratitude to you, and that of those who, along with me, in the gap between past and future, feel all the urgency of working in the direction you pointed out."

-Fragmento de una carta de Giorgio Agamben a Hannah Arendt en 1970, cuando el primero tenía 26 años. Tomado de Vivian Liska, "A Lawless Legacy: Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben", en M. Goldoni and C. McCorkindale, Hannah Arendt and the Law (2012) p. 80.

-Fragmento de una carta de Giorgio Agamben a Hannah Arendt en 1970, cuando el primero tenía 26 años. Tomado de Vivian Liska, "A Lawless Legacy: Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben", en M. Goldoni and C. McCorkindale, Hannah Arendt and the Law (2012) p. 80.26.11.12

Ten theses on Politics (J. Ranciere)

Thesis 1:

Politics is not the exercise of power. Politics ought to be defined on its own terms, as a mode of acting put into practice by a specific kind of subject and deriving from a particular form of reason. It is the political relationship that allows one to think the possibility of a political subject(ivity) [le sujet politique],3 not the other way around.

Thesis 2:

Thesis 3:

Politics is a specific rupture in the logic of arche. It does not simply presuppose the rupture of the 'normal' distribution of positions between the one who exercises power and the one subject to it. It also requires a rupture in the idea that there are dispositions 'proper' to such classifications.

Thesis 4:

Democracy is not a political regime. Insofar as it is a rupture in the logic of arche - that is, in the anticipation of rule in the disposition for it - democracy is the regime of politics in the form of a relationship defining a specific subject.

Thesis 5:

The 'people' that is the subject of democracy - and thus the principal subject of politics - is not the collection of members in a community, or the laboring classes of the population. It is the supplementary part, in relation to any counting of parts of the population that makes it possible to identify 'the part of those who have no-part'[le compte des incomptés]8 with the whole of the community.

Thesis 6:

If politics is the outline of a vanishing difference, with the distribution of social parts and

shares, then it follows that its existence is in no way necessary, but that it occurs as a provisional accident in the history of the forms of domination. It also follows from this that political litigiousness has as its essential object the very existence of politics.

Thesis 7:

Politics is specifically opposed to the police. The police is a ‘partition of the sensible’ [le partage du sensible] whose principle is the absence of a void and of a supplement.

Thesis 8:

The principal function of politics is the configuration of its proper space. It is to disclose the world of its subjects and its operations. The essence of politics is the manifestation of dissensus, as the presence of two worlds in one.12

Thesis 9:

Inasmuch as what is proper to 'political philosophy' is to ground political action in a specific mode of being, so is it the case that 'political philosophy' effaces the litigiousness constitutive of politics. It is in its very description of the world of politics that philosophy effects this effacement. Moreover, its effectiveness is perpetuated through to the non-philosophical or anti-philosophical description of the world.

Thesis 10:

The 'end of politics' and the 'return of politics' are two complementary ways of cancelling out politics in the simple relationship between a state of the social and a state of statist apparatuses. 'Consensus' is the vulgar name given to this cancellation.

Fragmentos de: Jacques Ranciere “Ten theses on politics’ in 5(3) [2001] Theory and Event pp 1-10.

25.11.12

Rosa Luxemburgo

Hace más de un año, presencié un panel de discusión sobre los movimientos sociales globales, el análisis de la primavera árabe, la crisis del capitalismo global, entre otros temas. Integraban el panel Slavoj Zizek, Etienne Balibar, Costas Douzinas y Drucilla Cornell. Como suelo hacer, tomé notas y luego me llamó la atención la mucha insistencia de Drucilla Cornell en la necesidad de, ahora más que nunca, decía, retomar el pensamiento de Rosa Luxemburgo. A un año y medio de eso, Rosa Luxemburgo y su pensamiento reaparecen en la genealogía que estoy trazando sobre la relación Derecho y "lo político". Hace unos días vi la película de Margarethe von Trotta sobre ella (Rosa Luxemburg, 1986) y la semana pasada pasé horas largas en un piso de la biblioteca dedicado a estudios Soviéticos e historia rusa. Cientos de libros, genialidad de fuentes bibliográficas, sus cartas mientras estuvo en prisión. Tanto ahí.

Hace más de un año, presencié un panel de discusión sobre los movimientos sociales globales, el análisis de la primavera árabe, la crisis del capitalismo global, entre otros temas. Integraban el panel Slavoj Zizek, Etienne Balibar, Costas Douzinas y Drucilla Cornell. Como suelo hacer, tomé notas y luego me llamó la atención la mucha insistencia de Drucilla Cornell en la necesidad de, ahora más que nunca, decía, retomar el pensamiento de Rosa Luxemburgo. A un año y medio de eso, Rosa Luxemburgo y su pensamiento reaparecen en la genealogía que estoy trazando sobre la relación Derecho y "lo político". Hace unos días vi la película de Margarethe von Trotta sobre ella (Rosa Luxemburg, 1986) y la semana pasada pasé horas largas en un piso de la biblioteca dedicado a estudios Soviéticos e historia rusa. Cientos de libros, genialidad de fuentes bibliográficas, sus cartas mientras estuvo en prisión. Tanto ahí.

No escuchada, olvidada y ninguneada por los 'suyos' por mucho tiempo, esta mujer y su pensamiento son hoy revisitados, y sus cartas, historias y debates principales en los adentros del socialismo, objeto de análisis minuicioso. Hoy, en el día de no más violencia contra la mujer, comparto este fragmento escrito por otra grande del Siglo XX, Hannah Arendt. Arendt, en Men in Dark Times, comenta una biografía de Rosa Luxemburgo y nos da luz sobre los detalles de su vida y obra. En este fragmento Arendt resume sus discrepancias con Lenin.

Porque el olvido y la invisibilidad de las mujeres y su pensamiento también es violencia. Salud!.

"The second point was the

source of

her disagreements with Lenin during

the First World

War; the first of her criticism of Lenin's tactics in the Russian Revolution of 1918. For she

refused categorically, from beginning to end, to see

in the war anything but the most terrible disaster, no matter what its eventual outcome; the price in human lives,

especially in proletarian lives, was too high in any event. Moreover, it would have gone against her grain to look upon revolution

as the profiteer of war and massacre-something which didn't

bother Lenin in the least. And with respect to the

issue of organization, she did not believe in a victory in which the

people at large had no part and no voice; so little, indeed, did she believe in holding power

at any price that she "was far

more afraid of a deformed revolution than an

unsuccessful one"-this

was, in fact, "the major difference between her" and the Bolsheviks. And haven't events proved her right? Isn't the history of the Soviet Union one long demonstration of the frightful dangers of "deformed revolutions"? Hasn't the "moral

collapse" which she foresaw-without, of course,

foreseeing the open criminality of Lenin's successor-done more harm to the cause of revolution as she understood it than "any and every

political defeat . . . in honest struggle against superior forces and in the teeth of the historical

situation" could possibly have done? Wasn't it true that Lenin was

"completely mistaken" in the means he employed, that the only way to

salvation was the "school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the

broadest democracy and public opinion," and that terror

"demoralized" everybody and destroyed everything?

She did not live long enough to see how right she had

been and to watch the terrible and terribly swift moral deterioration of the

Communist parties, the direct offspring of the Russian Revolution, throughout

the world. Nor for that matter did Lenin, who despite all his mistakes still had more in common with the original

peer group than with anybody who came after him. This became manifest when Paul Levi, the successor of Leo Jogiches in

the leadership of the Spartakusbund,

three years after Rosa Luxemburg's death, published her remarks on the

Russian Revolution just quoted, which she had written in 1918 "only for you" -that is, without intending publication.10 "It was a moment

of considerable embarrassment' for both the German and Russian parties, and

Lenin could be forgiven had he answered sharply and immoderately. Instead, he

wrote: 'We answer with . . . a good old Russian fable: an eagle can sometimes fly

lower than a chicken, but a chicken can never

rise to the same heights as an eagle.

Rosa Luxemburg ... in

spite of [her] mistakes .

. . was and is an eagle." He then went

on to demand publication of "her biography and the complete edition

of her works," unpurged of "error," and chided the German

comrades for their "incredible" negligence in this

duty. This was in 1922. Three years later, Lenin's successors had decided to "Bolshevize" the German

Communist Party and therefore ordered a

"specific onslaught on Rosa Luxemburg's

whole legacy." The task was accepted with joy by a young member named Ruth Fischer, who had just arrived from Vienna. She told the German comrades that Rosa

Luxemburg and her influence "were nothing less

than a syphilis bacillus."

….

One would like to believe that there is still hope for

a belated recognition of who she was and what she did, as one would like to hope that she will finally find her

place in the education of political scientists in the countries of the West.

For Mr. Nettl is right: "Her ideas belong wherever the history of political ideas is seriously taught."

-Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark Times (1955, 1968, pp. 53-56).

24.11.12

15.11.12

Consensus

“According to the reigning idyll, consensus democracy is a reasonable agreement between individuals and social groups who have understood that knowing what is possible and negotiating between partners are a way for each party to obtain the optimal share that the objective givens of the situation allow them to hope for and which is preferable to conflict. But for parties to opt for discussion rather than a fight, they must first exist as parties who then have to choose between two ways of obtaining their share. Before becoming a preference for peace over war, consensus is a certain regime of the perceptible: the regime in which the parties are presupposed as already given, their community established and the count of their speech identical to their linguistic performance. What consensus thus presupposes is the disappearance of any gap between a party to a dispute and a part of society. It is the disappearance of the mechanisms of appearance, of the miscount and the dispute opened up by the name “people” and the vacuum of their freedom. It is in a word, the disappearance of politics.”

J. Ranciere, Disagreement (p. 102).

9.11.12

Opúsculo: Acceso a la información

3.11.12

Nuestro 3er podcast en "Pensando el Derecho": Legitimación activa para grupos ciudadanos

Nuestro 3er podcast en "Pensando el Derecho". Escúchalo y compártelo:

En este episodio Érika Fontánez Torres, conversa con el licenciado Luis José Torres Aencio, abogado de grupos ambientalistas en casos ante el Tribunal Supremo, como el

En este episodio Érika Fontánez Torres, conversa con el licenciado Luis José Torres Aencio, abogado de grupos ambientalistas en casos ante el Tribunal Supremo, como el

del gasoducto, y profesor de Derecho de la UPR de la Clínica de Asistencia Legal. Fontánez Torres y Torres Asencio conversan sobre los desarrollos recientes del Tribunal Supremo de PR respecto a la doctrina de legitimación activa en casos de derecho ambiental impulsados por grupos de ciudadanos. Luego de detallar la última jurisprudencia, analizan cómo ésta afecta el acceso de la ciudadanía a los tribunales en busca de remedios.

» Podcast “Pensando el Derecho”: con Luis José Torres Asencio, Acceso a los Tribunales31.10.12

Presentación de: "Derecho al Derecho: intersticios y grietas del poder judicial en Puerto Rico"

Editora Educación Emergente

Editora Educación Emergentese complace en invitarles a la presentación del libro

Derecho al Derecho: intersticios y grietas del poder judicial en Puerto Rico

Érika Fontánez Torres e Hiram Meléndez Juarbe

escritores y compiladores

Lugar: Escuela de Derecho, Aula Magna

Día y Hora: Martes, 18 de diciembre 2012, 7:00pm

Presentan:

-Lcda. Ana Irma Rivera Lassén, Presidenta del Colegio de Abogados y Abogadas de Puerto Rico

-Arq. Miguel Rodríguez Casellas, Profesor Escuela de Arquitectura de la Universidad Politécnica

-Lcda. Amaris Torres Rivera, abogada comunitaria, exalumna y mentora del Programa ProBono de la Escuela de Derecho UPR

27.10.12

Nuevo libro: Paul Kahn piensa con Schmitt la soberanía y la teología política

Nos llega cortesía de nuestro colega y amigo, el Prof. Daniel Bonilla, de la Universidad de los Andes en Bogotá, Colombia, la nueva publicación de la serie Nuevo Pensamiento Jurídico (Siglo del Hombre Editores). Ya en otras ocasiones hemos comentado la excelencia de esa serie de publicaciones, que no debe faltar en la biblioteca de quienes tienen interés por examinar el fenómeno del Derecho y pensar sobre lo jurídico y lo político.

Nos llega cortesía de nuestro colega y amigo, el Prof. Daniel Bonilla, de la Universidad de los Andes en Bogotá, Colombia, la nueva publicación de la serie Nuevo Pensamiento Jurídico (Siglo del Hombre Editores). Ya en otras ocasiones hemos comentado la excelencia de esa serie de publicaciones, que no debe faltar en la biblioteca de quienes tienen interés por examinar el fenómeno del Derecho y pensar sobre lo jurídico y lo político.

En esta ocasión, Nuevo Pensamiento Jurídico publica en español el libro del Profesor Paul Kahn, de la Universidad de Yale: Teología Política: cuatro nuevos capítulos sobre el concepto de soberanía. En éste, Kahn examina, pensando con Schmitt, el concepto soberanía y su relación con el derecho para el contexto norteamericano. Pensando con Schmitt, más que pensando sobre él (la frase es del propio Kahn), Kahn centra su propósito en "interpretar discrecionalmente la Teología Política" (de Carl Schmitt).

Dejo la descripción del libro en su contraportada y más adelante un fragmento de la tabla de contenido. Ya comenzamos su lectura.

“El descubrimiento de la obra de Carl Schmitt ha sido desafortunadamente más político que filosófico. Kahn, profesor de Derecho en la Universidad de Yale, toma el enfoque opuesto: se concentra en una obra relativamente breve, pero fundamental, de Carl Schmitt, Teología política, con el fin de extraer las consecuencias filosóficas de las que el propio Schmitt podría no haber sido consciente. Es más, es capaz de hacerlo gracias a su profundo conocimiento de la teoría estadounidense del derecho. Al usar ejemplos provenientes de la experiencia jurídica estadounidense, muestra que el razonamiento radical que nutrió las elecciones políticas de Schmitt ─¡malísimas!─ se fundamenta en una filosofía de la libertad que únicamente se puede realizar cuando se garantiza la libertad de la filosofía. Kahn nos muestra que ese es el significado cardinal de la

“El descubrimiento de la obra de Carl Schmitt ha sido desafortunadamente más político que filosófico. Kahn, profesor de Derecho en la Universidad de Yale, toma el enfoque opuesto: se concentra en una obra relativamente breve, pero fundamental, de Carl Schmitt, Teología política, con el fin de extraer las consecuencias filosóficas de las que el propio Schmitt podría no haber sido consciente. Es más, es capaz de hacerlo gracias a su profundo conocimiento de la teoría estadounidense del derecho. Al usar ejemplos provenientes de la experiencia jurídica estadounidense, muestra que el razonamiento radical que nutrió las elecciones políticas de Schmitt ─¡malísimas!─ se fundamenta en una filosofía de la libertad que únicamente se puede realizar cuando se garantiza la libertad de la filosofía. Kahn nos muestra que ese es el significado cardinal de la

definición, tan a menudo citada como mal entendida, que hace Schmitt del soberano: 'Soberano es quien decide sobre el estado de excepción'. Los lectores de esta concisa obra hallarán que, al final, comprenden mejor el pensamiento de Schmitt, pero además que les ha ayudado a repensar los valores aparentemente manifiestos del pensamiento jurídico liberal. Tendrán el placer de observar como Paul Kahn reinterpreta el famoso argumento de Schmitt de que 'todos los conceptos centrales de la moderna teoría del Estado son conceptos teológicos secularizados' en el sincero diálogo que Kahn establece diestramente con Schmitt. Al evitar las largas discusiones académicas, la polémica política y la erudición exegética, Kahn ha escrito una obra crítica que une la política y la filosofía en una síntesis única”.

Dick Howard, Profesor Emérito de Stony University.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)

poder, espacio y ambiente's Fan Box

poder, espacio y ambiente on Facebook

.jpg)